Women in Science: What Sonam Mehrotra's studies on DNA replication and damage mean for cancer research

Editor's note: Starting National Science Day 2018, The Life of Science and Firstpost bring you a series profiling Indian women in Science. The challenges in Indian scientific life are many — more so for women taking up this path. This series honours those who beat the odds and serve as inspirations for the next generation of Indian science — a generation that is slowly and surely on its way to becoming gender equal.

By Sukanya Charuchandra

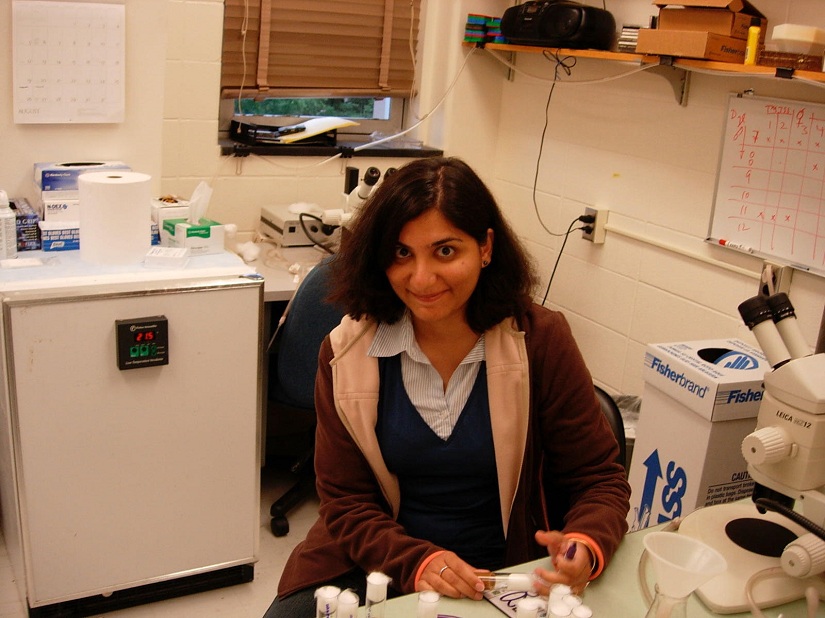

Sonam Mehrotra | 39 | Cancer Biologist | Tata Memorial Centre Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer (TMC-ACTREC), Mumbai

Walking through the green environs of Advanced Centre for Treatment, Research and Education in Cancer (ACTREC) in Navi Mumbai, I located Khanolkar Shodhika, the basic research wing where I was to meet Sonam Mehrotra, a cancer researcher. Her office is bare, representative of a new inhabitant, someone who is yet to make the space her own.

“I’ve had a little bit of a journey,” began Sonam, with a smile.

“A number of people in my family are PhDs in the sciences, so for me, it [a career in science] wasn’t something I chose out-of-the-blue.” Sonam grew up on the campus of IIT Kanpur, where her father was a professor in the metallurgy department.

She remembers fondly her time as an eight-year-old, exploring her father’s lab and weighing things in milligrams. Vacations with her botanist uncle and zoologist aunt at North Eastern Hill University, Shillong, meant hours examining biological specimens under the microscope and wandering through the campus observing the natural flora and fauna. “So the interest in science just developed over time,” she said.

Young Sonam moved away from her campus home to attend an undergraduate programme in human biology at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Delhi. A Master's programme in Biotechnology at Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU) of Baroda followed, topped by a PhD at Rutgers University and two postdocs in the US. Twelve years after leaving India, the memory of the “charming” campus life in India would pull her back to the country. This time to further her own research on DNA Repair.

Focused on forks

Sonam made a number of stops, but finally landed at a new lab with her research group at ACTREC in 2016. Her research could be pursued in any establishment with a molecular biology lab, but Sonam was always conscious that its ultimate application lay in tackling cancer. To meet this long term vision, she chose ACTREC. “My area of research was in DNA repair and replication, so I thought it would be a good idea to be in a cancer institute rather than in a teaching environment,” she said. Indeed, ACTREC provides her with access to patient samples and the opportunity to interact with clinicians.

Sonam’s work in cancer biology has evolved from her PhD and postdoctoral work in studying DNA replication and damage.

As cells multiply, so do our genes. This process of DNA — the genetic material — making copies of itself, is called replication. DNA is shaped by two strands wrapping around each other in a helix; a ladder of genetic code connects the two strands from the inside, much like a zipper. During the replication process, the strands are unzipped and a replication ‘fork’ forms. A toolkit of proteins, enzymes and raw material, together called the replication bubble, travels up the fork to prepare copies of the genetic material.

Replication is not always error-free. And often, the fork gets stuck. “But it’s not like every stalled fork leads to DNA damage,” Sonam pointed out. There are cellular mechanisms in place — genes and their protein products — that prevent the fork from stalling for a long time. One well-known gene involved is BRCA2 — a mutation in this gene is a marker for breast cancer susceptibility; another is RAD51 and the one that Sonam is most interested in is BCCIP.

During her time in Dr Zhiyuan Shen’s lab at the Cancer Institute of New Jersey, Rutgers, Sonam helped contribute to a discovery that BCCIP is required to maintain genome stability and plays a crucial role in repairing DNA damage. “I’ve asked various questions in this area since my PhD. What I do here [at ACTREC] is looking at another phenomenon called replication stress.”

“If the moving replication fork stops, even though molecules BRCA2, RAD51 and BCCIP try to prevent it, the cell experiences replication stress,” Sonam said.

Sonam’s current experiments try to pinpoint BCCIP’s role in this phenomenon.

Before and after replication stress

Picture two scenarios. In scenario one, a DNA molecule is being replicated. The fork moves along smoothly until at some point the fork stops. The cell experiences replication stress and in response, a machinery of proteins stabilises the fork and attempts to restart the process. The crisis is prevented. Everything resumes smoothly. In scenario two: The fork stalls for a prolonged period of time, the machinery this time is no longer effective, the fork collapses, there is DNA damage and DNA repair is necessary.

“Incidentally,” explained Sonam, “some of the key proteins needed to prevent replication stress and those involved in DNA repair are the same. Just that their functions are different [in the different scenarios].”

Sonam is inspired by the work of two eminent scientists in her field: Eva Petermann’s and Maria Jasin, who discovered the roles of RAD51 and BRCA2, respectively, in replication stress response. Their work revealed that these proteins are brought to the sites of stalled DNA replication forks and DNA damage. Dr Shen’s work showed that these molecules are recruited to the sites of DNA damage by another molecule — BCCIP, which stands for the BRCA2 and CDKN1A Interacting Protein. “In a way, I’m kind of following their footsteps and I’m trying to understand if BCCIP also plays a role replication stress response,” she explained patiently, slowly homing in on her current research question.

Just then the interview was interrupted by a phone call. After the short call, she said happily: “Oh! Our flies are here, from Hyderabad.”

BCCIP and Cancer

Sonam’s lab at ACTREC works with two systems – fruit flies and human cells. Not much is known about BCCIP but scientists are aware that patients with cancer, such as that of the breast and kidney, have mutant forms of the BCCIP protein. Anchoring to these clues, Sonam designs her experiments:

“When you mutate the BCCIP gene or decrease its level of expression in an experiment, you can see cells with a lot of genome instability, chromosome aberrations and breakage of chromosomes. My earlier work shows that BCCIP-deficient cells have a significant delay in restarting DNA replication and hence badly managed replication stress.” Without BCCIP, cells have to suffer a double whammy: they cannot stabilise forks and they cannot repair. “Which is what you see in a cancer cell,” Sonam pointed out.

High replication stress and error-prone DNA damage repair is a feature of precancerous and cancerous cells," said Sonam. This is very interesting for scientists like Sonam. “If we can find drugs which further increase replication stress, such that enough replication forks collapse in a cancer cell, the cancer cell can be made to die.” This could be a key into finding new ways to target and kill cancer cells that seem to have forgotten how to die.

Sonam is currently investigating if BCCIP can be manipulated to drive a cancer cell to death. She asks: “How can replication stress be modulated so that we can use it as a therapeutic avenue for cancer cells? Are there drug targets? Can we have drugs that can exacerbate replication stress? ”

Making many stops

Sonam has come a long way, but she still remembers her Master's at MSU being her “hardest years”. Nevertheless, she is grateful for the experience. Forced to make do with limited conveniences at MSU, her mastery with the minimal changed the way she looked at lab resources while abroad. She described an episode where her PhD advisor was throwing away chipped gel plates used to run experiments. Used to improvising by taping up chipped plates at MSU, Sonam knew that this sort of wastage could be prevented. “I told them it’s perfectly usable.”

At Rutgers, Sonam met her husband, then a graduate student in the department of mechanical engineering. “We met at a fire safety drill one evening when both of us were among the first residents to come out during the drill.” One son, two post-doctoral positions and 12 years after she first moved to the US, Sonam returned to Indian science. What inspired their return to India? “Mostly, the two-body problem,” she responded. Finding positions for both husband and wife on the same coast of the US had proved difficult, prompting them to look closer home. In the late 2000s, a number of new IITs were coming up in India and in 2012, they both found roles at IIT Jodhpur, as assistant professor(s).

However, settling down in a remote area was difficult and the shift, less than ideal. “For various reasons, we could not continue there. My son was not able to cope with the transition from US to Jodhpur,” said Sonam. Within the year, they found themselves moving yet again, this time to Pune. Her husband had secured a corporate position at a company in Pune, and she joined him though she did not yet have a job in Pune.

Soon enough, the restlessness kicked in. “It was very difficult for me to not do anything,” she said. Admittedly, the subsequent hunt for a job wasn’t easy, but it eventually led her to a position in Professor Sanjeev Galande’s lab in the Center of Excellence in Epigenetics at IISER, Pune. Sonam considers Prof Galande's support “invaluable” in her scientific journey. From IISER, she moved to ACTREC in 2016, keeping in mind the long-term vision of her research.

Lessons to be learned

It’s still early days for Sonam; setting up a new lab at ACTREC has not been that easy. “There is a procedure to everything,” she said, joking that even moving a table from here to there can be a process. Reagents and apparatus can take four to eight months to come, she added. “I’m still waiting for my equipment to arrive.” Keeping in mind these inevitable delays, Sonam is planning meticulously.

More than the sluggish pace, the lack of proper laboratory waste management systems in India shocks Sonam. “Nobody is thinking about it,” she lamented. She is of the opinion that with several new institutes coming up, people need to consider the environmental impact of pouring methanol, acetic acid, formaldehyde and every other kind of chemical you can think of down the drain. “All drains lead to the ocean,” she reminded. According to Sonam, a network needs to be established wherein every institution contracts out the collection and removal of these chemicals to agencies that can responsibly dispose of them.

India might have much to learn from the States when it comes to waste management, however, it does seem to be more progressive than the US with regards to maternity leave. While India offers paid maternity leave, the US provides no such benefits for employees. Earning a salary during pregnancy break is dependent on how many paid leaves the employee has stored up. During her second post-doctoral position in the US, Sonam was expected to return to work just six weeks after delivering her son. Any longer, and she would have risked losing pay.

“When you don’t have a support system like daycare centers, you end up taking care of a lot more outside your lab and you’re preoccupied with so many things,” she said. “Your efficiency in work is going to go down and that is why you see many women scientists not doing as well as their peer male scientists,” she concluded.